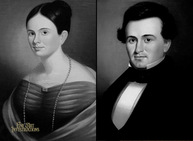

Recto – George Caleb Bingham

George Caleb Bingham, William Franklin Dunnica, ca. 1837

Oil on Canvas, 24 x 29 inches

Private Collection

Used with Permission

George Caleb Bingham, Martha Jane Shackelford, (Mrs. William Franklin Dunnica), ca. 1837

Oil on Canvas, 24 x 29 inches

Private Collection

Used with Permission

Early Years

William Franklin Dunnica was a 30-year-old merchant in Glasgow, Chariton County, Missouri, in 1837 when George Caleb Bingham painted the recently re-discovered portraits of him and of his 17-year-old wife, Martha Jane Shackelford.

A year later, the Missouri militia called Dunnica and other men from Chariton County to neighboring Carroll County where long-term residents and newly settled Mormons were ready to battle. Among the officers were Dunnica and Judge James Earickson. Both men urged compromise rather than bloodshed. Earickson negotiated a peaceful retreat for the Mormons who re-located to Caldwell County.((O. P. Williams, History of Chariton and Howard Counties, Missouri (National Historical Company. 1883), 54-56; Background information from Stephen C. LeSueur, “Missouri’s Failed Compromise: The Creation of Caldwell County for the Mormons.” Journal of Mormon History, Vol. 31, no. 2 (2005): 113-44. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23289934, accessed February 2019.))

As her husband helped forestall war, Martha Jane was at home with their newborn child, Jane Eliza (1838-1858). As was customary at the time, Martha Jane gave birth to a child about every year and a half: Ann Meyrick (1841–1863), Mary Louisa (1843–1930), Thomas Shackelford (1845–after 1880), Theodore (1847–1851), Locke (1851–1852), and Sydney (1855–after 1880).

Business and Civic Leader

William Dunnica operated his mercantile company in Glasgow for more than twenty years, partnering with various other businessmen. Simultaneously, he found foreign markets for tobacco locally grown by William Daniel Swinney and others. He also clarified titles for landowners. Among his clients was Kentucky Congressman Henry Clay.((O. P. Williams. & Co., History of Howard and Cooper Counties, Missouri (National Historical Company. 1883),437; Available documentation does not clarify whether Dunnica was the official or unofficial registrar for land titles; The Papers of Henry Clay: The Whig Leader, January 1, 1837-December 31, 1843 (University Press of Kentucky, 2015), 453.))

Methodist Church

When the Methodist church was organized at Glasgow on December 28, 1844, the trustees included William Dunnica and William Swinney. The issue of slavery had split the Methodist church nationally into two branches, the northern and the southern. Less than six months after the founding of Glasgow’s First Methodist Church, trustees had to decide which division to join. Dunnica, like the majority of Missourians, who if not southern-born, had southern roots, owned slaves. His numbered 10, and ranged in age from 1 to 50. They lived in three slave houses. With the rest of the trustees, he voted for membership in the Methodist Episcopal Church South.”((Williams, History of Chariton and Howard Counties, Missouri, 354.))

From April 1849 until December 1852, William Dunnica held the position of postmaster, a prestigious federal appointment at the time. In 1858, Glasgow citizens organized a branch of the Exchange Bank of St. Louis with Dunnica as its leader. In the midst of William’s successes, Martha Jane died in childbirth on August 31, 1858. Their seventh child died with her.

Second Wife

Almost two years after Martha Jane’s death, on June 30, 1860, William married Leona Hardeman Cordell (1823-1905) in St. Louis, Missouri. Leona was the daughter of John Hardeman (1776-1829) a merchant, trader and businessman who was also a famed amateur botanist. Her first husband, Richard Lewis Cordell, had abandoned her and their two children. Her marriage to Dunnica would last until his death in 1896 – a total of 36 years.((William E. Foley, “Hardeman, John,” in Lawrence O. Christensen, William E. Foley, Gary Kremer, and Kenneth H. Winn, eds., Dictionary of Missouri Biography (University of Missouri Press, 1999), 370-371. George Caleb Bingham portrayed Leona’s brother, John Locke Hardeman, circa 1855, which is owned by the State Historical Society of Missouri, Columbia, http://digital.shsmo.org/cdm/singleitem/collection/art/id/245/rec/1, accessed January 2019.))

For a still longer biography, including details of the Civil War in Fayette, Missouri, and Bloody Bill Anderson, follow this link: Stories Behind the Portraits: The Dunnicas.

Last Years

After the war, William and Leona Dunnica repaired their home and replaced their bullet-ridden furniture. Under the clapboard of the house, the bullet holes can still be seen. The Thomson & Dunnica Bank survived the conflict and continued until 1877 when it merged with Howard County Bank. Dunnica again led the financial institution until he retired in 1881 at the age of 74.

In 1883 a biographer wrote, “Mr. D. has been an enterprising and public-spirited citizen and has contributed very materially to the general prosperity of Glasgow and surrounding country. He has never sought or desired office, although he has several times been induced to accept minor official positions that did not interfere with his business. His desire has been, so far as public affairs are concerned, to make himself a useful factor in the material development of the county with which he is identified. The biographer admonished his readers that the life of W. F. Dunnica proved that “intelligent industry and frugality, united with upright conduct, cannot fail to bring abundant success.”((J. Y. Miller, Battle of Glasgow History, Lewis Library, Glasgow, Missouri, http://www.lewislibrary.org/BOG.html, accessed January 2019; email correspondence with J. Y. Miller, January 28, 2019.))

William Franklin Dunnica lived to the age of 88. He died on April 28, 1896. He and his wives are buried in Glasgow’s Washington Cemetery.

Verso 1 – Sara

In 1847, Leona Hardeman Cordell, the woman who would become the second wife of William Franklin Dunnica, rented her eight-year-old slave girl, Sara, to an Edwin Tanner. At the time Leona was a 25-year-old woman with two small children who had been abandoned by her husband. She and the children had moved to St. Louis to the home of her mother, Nancy Knox Hardeman Dunnica and her stepfather, James Dunnica, uncle of her future second husband. Judge Dunnica owned the equivalent of $3 million in real estate. Why was it necessary to rent out Sara?((United States Census Bureau, Seventh Census of the United States, “Household of James Dunnica,” St. Tammany Parish, Louisiana, August 17, 1850, page 47, lines 44-48.))

Warning: graphic violent details

In August 1847, Tanner returned Sara to Leona. “The flesh on the back and limbs were beaten to a jelly – one shoulder bone was laid bare – there were several cuts from a club, on the head and around the neck was the indentation of a cord, by which it was supposed she had been confined to a tree…After coming home, her constant request until her death was for bread, by which it would seem that she had been starved as well as unmercifully whipped.”((Frazier, 141-142; Union (St. Louis, Missouri) August 16, 1847, 3:1; Missouri Republican, August 16, 1847, 2:2; “Inquest: Slave Sarah,” Coroner’s Report of Inquests, 1838-48, Missouri Historical Society.))

The coroner called six men to James Dunnica’s home to view the dead girl’s body. They unanimously swore under oath that Sara “came to her death by violence inflicted on her person.” The coroner wrote, “the above-named Sara was evidently whipped to death, probably and almost certainly by Edwin Tanner or some of his family or by himself and family.” The coroner then added this highly personal note, ‘Of all the inquests that I have held, numbering 317, and having seen, as I thought, the work of death in almost all its horrors, the above crime far surpasses anything I have ever seen of human depravity and cruelty.” Tanner may have been fined. He was not hanged or imprisoned.((Ibid.))

Verso 2 – Charlie and Stephen; William and Telly

Leona’s older half-brother, John Locke Hardeman lived in Saline County, Missouri. In 1855 or 1856, George Caleb Bingham painted his portrait, which is now owned by the State Historical Society of Missouri. In 1857, Hardeman died. He was 48. In his will, he wrote that his slaves “Charlie and Steven, and their families, not be broken up.” To his half-brother, Glen Owen Hardeman, he left many possessions, including his “old faithful servants,” William, 63, and Telly, 60. Locke also provided $1,000 (about $12,000 today) to ensure their comfort for the rest of their lives. Why not free all his slaves as another portrait sitter Lewis Penn Witherspoon Balch did? Why not give William and Telly the $12,000? In 1858, in Missouri’s Little Dixie, such a thought was probably unthinkable. Indeed, in 1858, Hardeman’s actions were radical.