George Caleb Bingham

A Biographical 21st Century Interpretation

"There is no honorable sacrifice which I would not make to attain eminence in the art to which I have devoted myself. I am aware of the difficulties in my way; …by determined perseverance I expect to be successful."

"I am, sir, a Republican, a Democrat, in the true and legitimate sense of those terms, being governed by that principle which urges us to submit with due deference to the omnipotence of the popular will."

"… honesty and capacity, rather than party servility, will be the qualifications for office. But I forget that I am a painter and not a politician."

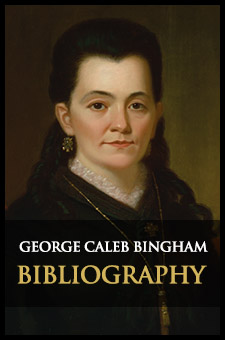

George Caleb Bingham

Self Portrait, 1834

Saint Louis Art Museum

Eliza McMillan Trust, Accession No. 57:193

Used with permission

George Caleb Bingham was an artist and a man of uncompromising principles. George Caleb Bingham depicted the people and the world around him with unparalleled honesty. His sincerity imbued his paintings with timeless authenticity expressed with increasing technical skill and colors uniquely his own. He helped shape a nation’s vision of itself. More than 200 years after his birth, art reviewers throughout America describe Bingham as one of the country’s best artists. His reputation surpasses the most prestigious painters of his day. His paintings hang in museums across the nation. Public institutions select his work to represent American art throughout the world.

Bingham was born March 20, 1811, when the country was still young. Words of the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights were fresh. Even when the world changed around him, he lived by the principles of the country’s founding documents and had no patience with those who did not. Throughout his life, he worked for a national system that included a limitation of slavery and a union of states. He was committed to civil liberties and education. He held office as a state legislator, state treasurer, school board member, police commissioner, and Adjutant General. In those roles, he advocated reason, not partisanship. He preserved state funds, exposed corruption, stopped vigilantism, and sought fair compensation for injustice.

During his lifetime, George Caleb Bingham painted over 300 portraits, nearly 60 genre paintings, (painting of everyday life), and more than 30 landscapes. After his death, memory of him faded. Art historian Fern Helen Rusk tenaciously preserved his artistic legacy in a small volume published in 1914, George Caleb Bingham: The Missouri Artist. Twenty years later, in the midst of the Great Depression when Populism and Regional Art were at their peaks, Bingham’s realism and his representations of the common man found resonance. At the City Art Museum of St. Louis in 1934, Meyric R. Rogers exhibited the work of George Caleb Bingham. Early the following year, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York re-introduced him to a national audience. Albert Christ-Janer studied Bingham in the 1940s while most of the art history texts of the decade overlooked him.

In the mid-1950s, art historian Edgar P. Richardson wrote:

Bingham saw the grand meaning of the commonplace. What is more extraordinary, he was able to create…a style of great visual poetry – a large and almost archaic severity of drawing, brilliantly luminous, yet smoky in color and extremely subtle in its gradations of light and air. And over all there is a mood of grandeur and solemnity in his work, as if he would say to his fellows: This is a heroic age…

His best works were done in a period extending not much over ten years. In 1856 he went abroad to study at Düsseldorf, the seat of a German school of literary-sentimental narrative painting which had begun to have a great reputation in America in the fifties… His work was there infected to some extent with sentimentality and overemphasis; at least, it did not gain. When he returned in 1859, the Civil War was about to burst upon us. Bingham was a man of strong Union convictions. He threw himself into the political struggle in his native state.[1]

Countless iterations of that latter assessment followed, often reduced to one sentence, such as: “Unfortunately, on returning home, his style deteriorated due to an adoption of a dry academic technique,” or phrased as "Bingham created his best work in the 1840s." Omitted is the significant fact of the turmoil of the 1860s.[2]

Did a “dry, academic technique” cause his style to deteriorate?[3] Bingham returned to America on the eve of the Civil War to Kansas City, where since 1854, lawlessness and violence had raged at the Missouri-Kansas border. He pleaded with the federal officials to intervene. But the government in Washington, D.C., ignored him. With pillage and murder unchecked, many previously neutral Missourians joined the rebel cause, as Bingham had warned. More violence ensued. Escalation brought murder of hundreds and desolation for miles. Bingham poured his emotions into one of his few post-war genre pieces, Order No. 11.[4]

George Caleb Bingham

Martial Law or Order No. 11 (2) 1869

State Historical Society of Missouri

Columbia, Missouri

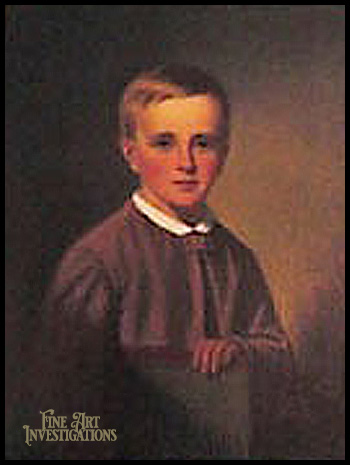

George Caleb Bingham

James Rollins Bingham, 1870

Oil on Canvas, 28 x 24 inchesPrivate Collection

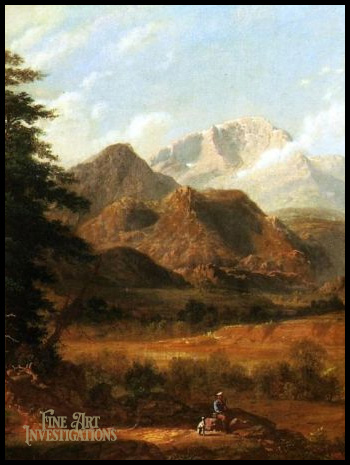

George Caleb Bingham

View of Pikes Peak 1, 1872

Oil on Canvas, 28 x 42 inches Amon Carter

Museum, Fort Worth, Texas

George Caleb Bingham

Thomas Hoyle Mastin, 1871

George Caleb Bingham

Palm Leaf Shade, 1878

Oil on Canvas, 26 x 22 inchesPrivate Collection

George Caleb Bingham

Little Red Riding Hood (Miss Eulalie Hockaday), 1878

Oil on Canvas, 49 x 37 inchesPrivate Collection

George Caleb Bingham

Miss Vinnie Ream, c. 1876

Oil on Canvas, 40 x 30 inchesState Historical Society of MissouriColumbia. Missouri

George Caleb Bingham

The Puzzled Witness, 1874

Oil on Canvas, 23 x 28 inches

Private Collection (Detail)

Like most Americans, Bingham felt the pain of Civil War. He could no longer paint brilliantly luminous, heroic scenes. Near the end of his life, Bingham represented himself as the central character in an overlooked genre work, The Puzzled Witness, 1874. In this subtle self-portrait, he placed himself as a simple witness in uncomfortable surroundings. George Caleb Bingham had witnessed history in the making. He had preserved history in enduringly beautiful paintings. He had participated in history's creation.[6] But at the end of his life, what was he to make of all that he had witnessed?

Bingham depicted not only the antebellum world of America with perceptive clarity, but also Civil War and Reconstruction. Inherent in his later pieces are complex questions that still plague the nation: centralization vs. de-centralization, civil liberties vs. civil order. The questions are hard ones. Devoting as much time to Bingham’s post-war pieces as to his antebellum might open doors of discussion and, perhaps someday, to answers.

Fine Art Investigations is devoted to locating all portraits of George Caleb Bingham and to telling the stories behind them within historical context. Both projects are works in progress.

Footnotes

[1] E. P. Richardson, Painting in America; the story of 450 years, (New York: Crowell, 1956), 176

[2] Nicola Hodge and Libby Anson, The A-Z of Art: The World’s Greatest and Most Popular Artists and Their Works, (Berkeley, California: Thunder Bay Press, 1996) and Ian Chilvers and Harold Osborne, The Oxford Dictionary of Art (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), reduces E. P. Richardson’s assessment to “his work lost much of its racy freshness and charm, becoming overlaid with sentimentality”, page 64. Another iteration is found in Matthew Baigell, A Concise History of American Painting and Sculpture, (New York: Harper & Row, Publishers, 1984), 106: “Unfortunately he learned there to turn his compositions into sweetened, staged tableaux, with posed actors in place of vital, ordinary people.”

[3] An alternate opinion is that “In Düsseldorf…, the technical subtleties he absorbed seem to have disturbed the cohesive force of his vision. Bingham had been moving away from his original inspiration before he went abroad, and Düsseldorf merely reinforced the faults of his style” in Milton W. Brown, Sam Hunter, John Jacobus, Naomi Rosenblum, David M. Sokol,, American Art: Painting, Sculpture, Architecture, Decorative Arts, Photography, (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., Publishers, 1979), 224

[4] Other post war genre paintings by Bingham are General Nathaniel Lyon and General Preston Blair Starting from the Arsenal Gate in St. Louis to Capture Camp Jackson, 1865; Major Dean in Jail, 1866; and The Puzzled Witness, 1874

[5] Connoisseur Paul Kossey discovered a new George Caleb Bingham landscape, which is pictured and described in detail in “George Caleb Bingham: A Landscape Discovery,” The Magazine Antiques , November /December 2014 issue

[6] Just as art historian Fern Helen Rusk resurrected Bingham from artistic oblivion in 1914 with her book, George Caleb Bingham, The Missouri Artist, historian Paul C. Nagel resurrected Bingham’s political contributions in 2005 in George Caleb Bingham: Missouri’s Famed Painter and Forgotten Politician.