Wilhelm Heinrich Funk

American Artist 1866-1949

Art critics of his day praised his “fearless freedom of brushwork… general gusto, and joyousness and decorative style.” Why is Wilhelm Heinrich Funk nearly forgotten today? The reasons are many, but perhaps most importantly, justly or unjustly, he was on the wrong side of history. [1]

Wilhelm Heinrich Funk was born in Hanover, Germany, on January 14, 1866. At the age of 19, in May 1885, he immigrated to the United States. Charlotte, North Carolina was his home in 1889. In the spring of 1890, he traveled to Europe and on his return in July, he applied for American citizenship. On October 21, 1890, the Superior Court of Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, granted his request for naturalization noting that he “behaved as a man of good moral character, attached to the principles of the Constitution of the United States,” and that “he renounces forever all allegiance and fidelity to every foreign prince, potentate, state or sovereignty, whatever, and particularly to William the II, Emperor of Germany, of whom he is now a subject.”[2]

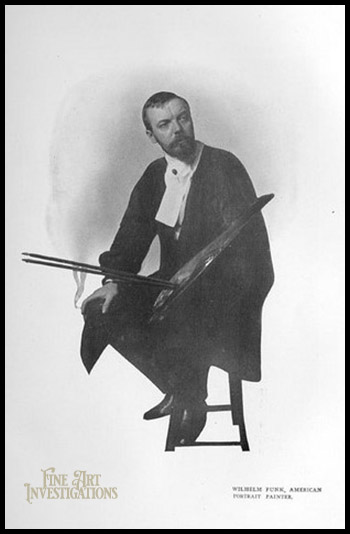

Funk had studied at the Royal Academy in Munich, in France and Italy, and at the Art Students League in New York. He worked as an illustrator for the New York Herald and at various American magazines. He considered himself an American artist. Under a self-portrait, he inscribed, “Wilhelm Heinrich Funk, An American Portrait Painter.”

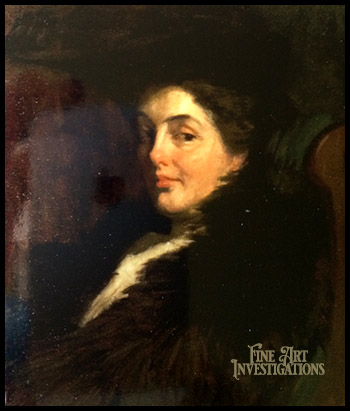

Attributed to Wilhiem Heinrich Funk

Lilian De Peyster Post (Mrs. John Arthur Pulsford), ca. 1903

Oil on Canvas, 22 x 18 inches

Private Collection

In 1905, the New York Times devoted nearly a full page to Wilhelm Funk and his artwork. Critic Charles de Kay wrote, “Mr. Funk is one of those Germans whose artistic life has been passed outside the Fatherland. For the last fifteen years he has been to all intents and purposes an American.” When McKay had tried to elicit quotes from Funk about German art, German artists, and members of the German community who had posed for him. Funk expressed appreciation for Expressionism, but otherwise distanced himself from other Germans.[4]

Funk traveled to Europe each spring or summer. In Paris and London, notable personages commissioned him for portraits. In New York in winters, he hosted musicales and costume balls at his studio on West 42nd Street. Celebrities, who sometime doubled as his portrait subjects, entertained the guests. They performers included internationally acclaimed operatic soprano Madame Nordica (1857 –1914). folklorist and actress Kitty Cheatham (1864 –1946), impressionist Elsie Janis (1889 –1956), and members of the New York Symphony Orchestra. His guests stepped from the pages of the social register: the John H. Flaglers, the H. O. Havermeyers, the Frederick Vanderbilts, the Richard W. Gilders, and the publisher Peter F. Collier. Also in the audience were real and pretended royalty such as, Viscountess Maitland, Baroness Salzberger, and Prince del Drago; and members of the aristocracy of the art world: artist Edwin Blashfield (1848-1936), art school founder Mrs. Dunlap Hopkins, and Sir Purdon Clarke (1846-1911), former curator of the Victoria and Albert Museum, whom J. P. Morgan hired to lead the Metropolitan Museum of Art. At midnight, Funk served full-course dinners. [5]

Wilhelm Funk

Mrs. James Lindsey Gordon and her daughter Dorothy ca. 1905

Wilhelm Funk

Miss Sara Wiborg, ca. 1905

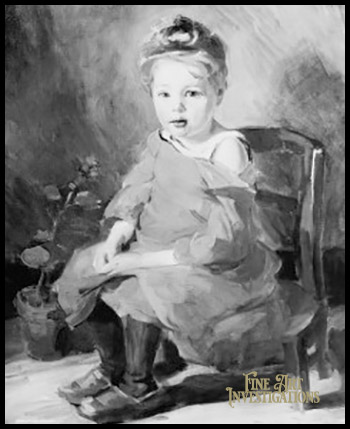

Wilhelm Funk

Mrs. Ernest Wiltsee and Child, 1909

Wilhelm Funk

Lady Elcho, ca. 1905

Rejected by the art establishment of his adopted country, Funk arranged a series of exhibitions in Europe. In June 1913, he traveled to Paris where the American ambassador to France, Myron T. Herrick (1854 –1929), opened the exhibit at a gallery in the Place Vendome. While in France, Funk painted portraits of the Minister of Fine Arts and of the owner of the Paris Journal. His collection moved on to shows in London, the Riviera, Berlin and Munich. In Berlin, German nobles and a hotel owner sat for portraits. When World War I began, Funk escaped Germany for Italy, where he applied for a passport to return to the United States. [7]

While Funk circuitously made his way home, his paintings continued on their tour. In January 1915, Funk received word that the Association of Munich Artists had elected him a special member. In April his paintings still in Europe were shipped from Berlin to Bremen to the steamship Ogeechee, operated by the Mallory Line, a firm based in Savannah, Georgia, One day out of port, the British seized the ship and confiscated its cargo. American Art News reported, “Mr. Funk is indignant over the seizure because he says he is an American citizen and painted most of these portraits in this country…They were his property when he took the collection abroad and he is the more irritated because the portraits were placed on view for the British public and should have been identified by destination as the American property of an American.”[8]

Wilhelm Funk

Sir Caspar Purdon Clarke, 1906

Wilhelm Funk

La Petite Angeline

The following year, in February 1916, a reporter from American Art News reviewed Funk’s show at New York’s Reinhardt Galleries. He questioned the artist’s “tact and taste,” for displaying his Berlin portraits during war, but wrote that he was at the “zenith of his powers,” and admired his “strong fine brushwork and rich truthful color.” The reviewer particularly praised a portrait of three girls as “a modern Gainsborough in composition and handling.” That painting is lost, but a print of La Petite Angeline is one of the few extant examples that shows Funk’s facility in painting children.[9]

The World War ended on November 11, 1918. On June 19, 1919, “Wm. H. Funk ” applied for a passport to England, France, Holland, and Germany, if possible, to (1) retrieve his confiscated paintings, valued at $35,000 in order to return them to their owners and (2) “to get his mother which he left over there on account of difficulty of getting passage in 1914 after war began…As she was over eighty years of age, I decided to leave her there. I have had no communication from her since that time and do not know whether or not she is alive.” His application was rejected by the State Department with a statement that passports were not being issued to Germany. Funk’s friends wrote in his support, referring to him as “William.” A staff member of the Department of State suggested Funk should defer his trip “until conditions were more normal.” Funk persisted. A State Department official wrote to North Carolina for verification of his naturalization. The confirming papers, and payment of a dollar, secured his passport.[10]

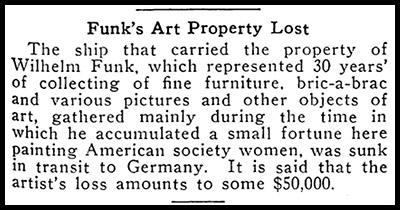

A little over six months later, American Art News reported:

Wilhelm Funk, for over twenty years an American citizen…whose art was recognized and appreciated here…has recently purchased a castle near Munich, Germany, which he has remodeled into a palatial home and studio. He writes that he is extremely happy in the “Fatherland.” …He is said to have written that he will never return to the U.S.[11]

The following month, the same source published:[12]

Funk never returned to his chosen country. He remained in the country of his birth until his death in 1949. Was his decision for self-imposed exile due to a renewed love of his original homeland or was anti-German sentiment combined with bad luck the reason? Does he deserve to be forgotten or to be remembered?

Footnotes:

“Art News and Notes,” New York Times, January 16, 1910, page 14, col. 1-2.

2. Peter C. Merrill, German Immigrant Artists in America (Scarecrow Press, 1997), 69-70; U.S. Customs Service, Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1820-1897, M237, Roll 551; List Number 995, Line: 41; J. W. Morrow, Clerk of the Superior Court, Mecklenburg County, State of North Carolina, Statement of Naturalization,” in Passport Applications, January 2, 1906–March 31, 1925. National Archives Records Administration, M1490, Roll 844, p. 483.

3. “Portraits by Wilhelm Funk,” New York Times, January 5, 1902, page 24, col. 2.

4. Charles de Kay, “German -Americans as Artists and Art Lovers,” New York Times,January 8, 1905, Part 4, page 1, col. 1-5.

5. Nordica Memorial Association, “Lillian Nordica: America’s Greatest Diva,”http://www.lilliannordica.com/, accessed June, 2016; “Nordica, Lillian,” cantabile – subito,http://www.cantabile-subito.de/Sopranos/Nordica__Lillian/nordica__lillian.htm, accessed June 2016; “Kitty Cheatham,” Broadway Photographs,http://broadway.cas.sc.edu/content/kitty-cheatham, accessed June 2016; Ohio State University Libraries, “Elsie Janis and Her Gang,” Ohio State University Exhibitions,https://library.osu.edu/projects/elsie-janis/thegang.html, accessed April 2016; “European Portraits and a Musicale,“ New York Times, December 31, 1905, page 8, col. 6; “Costume Party in a Studio,” New York Times, April 4, 1906, page 9, col. 2; “Wilhelm Funk’s Musicale,” New York Times, January 30, 1907, page 9, col. 3.

6. American Art News, October 18, 1911, page 1; Peter Hastings Falk, “Funk, Wilhelm,”Who Was Who in American Art (Sound View Press, 1985), 220; Sarah J. Moore, John White Alexander and the Construction of National Identity (Associated University Presses), 2003.

7. National Archives and Records Administration (NARA); Washington D.C.; NARA Series: Emergency Passport Applications, Argentina thru Venezuela, 1906-1925; Box #: 4675; Volume # 171: Italy

8. American Art News, Vol. XIII, No. 13, January 2, 1915, page 4, col. 3; New York Times,April 29, 1915, page 9, col. 4-8.

9. American Art News, Vol. 14, No. 20, February 19, 1916, page 2, col. 3.

10. National Archives and Records Administration (NARA); Washington D.C.; NARA Series: Passport Applications, January 2, 1906 – March 31, 1925; Roll #: 844; Volume #: Roll 0844 – Certificates: 99500-99749, 24 Jul 1919-24 Jul 1919.

11. American Art News, Vol. 18, No. 18, February 21, 1920, page 1, col. 1.

12. American Art News, Vol. 18, No. 23, March 27, 1920, page 1, col. 1.