William James Hubard

American Artist 1809-1862

Born in England [1] on August 20, 1807, William James Hubard learned to be a showman while still a boy. His precociousness for cutting recognizable silhouettes caused his parents to give him over to the care of a neighbor, Smith, who placed him with a traveling band of performers. Between musical interludes, Hubard cut intricate forms or life-like portraits from black paper on tours throughout Great Britain. His manager brought him to America in 1824 when he was 15.[2]

Hubard was fortunate enough, while in New York, to make the acquaintance of a young man who would become one of the most talented artists of the early United States, Robert Walter Weir (1803-1889). Weir, 20, was about to leave the city to study in Europe. Weir encouraged the teenager, so facile with scissors, to try his hand at oil painting. Weir even gave Hubard his painting supplies. Not long after, Hubard accused his manager of exploiting him and ventured out on his own.[3]

Hubard used Weir’s tools, but first needed to create his own profits through his original medium. In January 1826, in Philadelphia, “Master Hubard” opened the Hubard Gallery. He exhibited 136 silhouettes. In interviews, he reduced his age by two years and claimed his maternal grandfather to be a famed German sculptor. He pointed to paper likenesses of the Duchess of Kent and her children, Charles, Feodor and Victoria, and related anecdotes of his personal meetings with them. He said the Duchess treasured his silhouette of Swan in Bulrushes. Among the silhouettes were landmarks, such as Westminster Abbey; of diversions, like duck-hunting; and portraits of personages as diverse as General Lafayette and George III. Among the many poems Hubard’s silhouettes inspired was:[4]

William James Hubard

Miss Barton, ca. 1845

Oil on Canvas, 29.5 x 24.5 inches

Private Collection

THE HUBARD GALLERY

Here with strange mysterious hand

HUBARD waves his fairy wand

At whose bidding forth there comes

Chapels spires and princely domes

At whose wink the forests rise

Castles hills and plains and skies

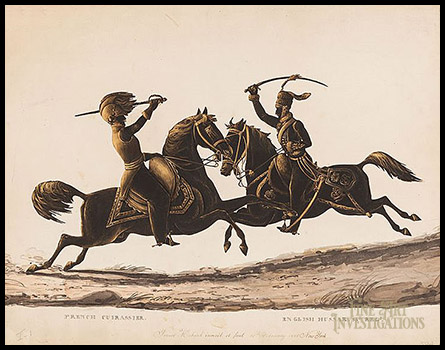

Horsemen fierce on fiery steeds

Rushing on where glory bleeds [5]

William James Hubard

Military Silhouette of French Cuirassier and English 15th Hussar, 1825

Private Collection

William James Hubard

Charles Carroll of Carrollton, ca. 1831

Metropolitan Museum of Art, 56.207

Rogers Fund

www.metmuseum.org

That same year, Hubard displayed paintings at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. The Boston Athenaeum later accepted his work. His paintings attracted the attention of Gilbert Stuart and Thomas Sully, who like Weir, encouraged his talent.[6]

In keeping with his experience as a silhouettist, Hubard’s first oil paintings were “cabinet size,” for example, his portraits of Supreme Court Justice John Marshall at the National Portrait Gallery and art collector Robert Gilmer, Jr. at the Baltimore Museum of Art, and Charles Carroll of Carrollton. As he transitioned from black paper to colored paint, his palette was dark; his figures, so two- dimensional as to look almost like paper cut-outs. He posed his sitters as though seen from a distance and illuminated them with a solitary bright light source. Yet another vestige of his past medium was detailed fine lines. But, simultaneously, he was moving to a portraitist’s psychological engagement with his subject. In Hubard’s representation of Dr. William P. C. Barton, he moved closer to his subject, gave him greater substance and added more color. Barton was an artist in his own right with botanical illustrations, a fact that may have inspired Hubard to create an artwork that is, arguably, superior to others from the same period. It was not surprising that more than a decade later, the physician-botanist and his wife, Elizabeth Rittenhouse Sergeant, chose Hubard to portray one of their daughters.

In the years between Barton portraits, the artist had moved south to Virginia. He painted portraits in Norfolk, Williamsburg, and Gloucester County. In Gloucester, he met and married Marie Mason Tabb, from an old and wealthy Tidewater family. Shortly after their wedding in 1837, the couple sailed across the Atlantic. During their two years abroad, Hubard studied in Paris, Milan and Florence. In Florence, he and Marie became friends with American sculptors Hiram Powers and Horatio Greenough. [7]

They returned to the United States in June, 1839. Back in Gloucester, Hubard painted portraits, including members of his wife’s family, Henry Wythe Tabb and Harriet Tabb, and later in Richmond, two daughters of an attorney, Joseph Mayo, who would later be mayor of the city. An image of the second portrait, Henrietta and Sarah Mayo, shared by an expert on Hubard, confirmed the identity of the artist of Miss Barton.[8]

By February 1844, the Hubards were in Philadelphia, where on the 8th of that month, their son, William James, Jr., was born. The artist probably painted Miss Barton near that date. Miss Barton is a full-size, 29.5 x 24.5 inch, oil on canvas painting. It, along with the portrait of the Mayo sisters, is a fine example of the artist’s mid-career work and proof of William James Hubard’s maturity as an artist, a maturity he achieved through hard work. Attention to fine detail was still part of his artistic repertoire, as can be seen in the Miss Barton’s lacework and jewelry, but gone were the almost stick figures, the strange anatomy, and distant perspective. All three sitters are well-placed on the canvas, have substance, depth, and a psychological connection with the viewer.

From Philadelphia, the Hubards went to New York City. They lived at 14 Warren Street. Their daughter Ella was born there in July 1847, the same year that the National Academy of Design accepted eight of the artist’s paintings for exhibition.[9]

Eventually, the family made their way south again. In Richmond, Virginia, James Hubard built a home and studio in the fields outside the city, now the location of Virginia Commonwealth University. He owned eight slaves. His friends included his near neighbor, Edward Peticolas, a member of a long-established artistic Virginia family, and Mann Satterwhite Valentine II, a wealthy and multi-talented merchant who later founded the Valentine Museum. Mann and Hubard wrote an opera, “Amadeus,” that Hubard commemorated with a painting entitled Amadeus or A Night with the Spirit. (Valentine Museum.) [10]

William P. C. Barton

“Liriodendron Tulipifera” (Tulip Tree)

Plate 8 from William P. C. Barton, Vegetable materia medica of the United States, or, Medical botany: containing a botanical, general, and medical history of medicinal plants indigenous to the United States, Illustrated by coloured engravings, made after drawings from nature, done by the author

( H.C. Carey & I. Lea), 1825

William James Hubard

Henrietta and Sarah Mayo, ca. 1840

Courtesy of Valentine Museum, V.57.184.01

Richmond, Virginia

William James Hubard after Jean-Antoine Houdon

George Washington, 1857

Bronze North Carolina State Capitol

Raleigh, North Carolina

At the pinnacle of his career as a painter, as evidenced by his 1850 portrait General George Washington, Hubard turned to sculpture. He built a foundry to produce bronzes of Jean-Antoine Houdon’s marble statue of George Washington, with the blessing of Virginia legislature. At the time, only one sold, which brought him to the brink of financial ruin. Hubard’s bronzes of George Washington are now displayed at the United States Capitol, the North Carolina State Capitol, Miami University, Virginia Military Academy, the City of St. Louis, and the Smithsonian. In 1861, in addition to monetary worries, the country was on the verge of war. To re-coup his losses, Hubard re-fitted his foundry into a factory that manufactured Brooke rifles for the Confederacy. On February 13, 1862, he was injured in the gruesome factory accident and died two days later. He was 54.

In the aftermath of the war, those who killed Union soldiers, directly or indirectly, were reviled by northerners, including academics. Perhaps because he was a southern sympathizer, art historians who later wrote of Hubard chose to focus on his personal shortcomings rather than on his art. A fresh perspective may be to put aside the argumentum ad hominin, as is the usual case with artists, to consider his accomplishments. With help from those who appreciated his talent, William James Hubard transformed himself from performing paper cutter to Tidewater Virginia’s premier artist. Simply looking at the evolution of his art over his somewhat abbreviated lifetime speaks to his genius. The Valentine Museum in Richmond, Virginia, owns the largest public collection of his art. Numerous private individuals own his paintings. How many American artists, whose name is not instantly recognizable, could claim their work is owned by so many prestigious institutions: United States Capitol, Baltimore Museum of Art, Brooklyn Museum, College of William and Mary, Colonial Williamsburg, Gibbes Museum of Art, Johnson Collection, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Museum of Fine Arts – Boston; Philadelphia Museum of Art, Smithsonian Institution, University of Virginia – Charlottesville, and Yale University Art Gallery? William James Hubard is one of the few.

Footnotes:

1. Some biographies give Hubard’s birth location as Shropshire; others, as Warwickshire.

2. Atkinson and Alexander, A Catalogue of the Subjects contained in the Hubard gallery: to which is prefixed a brief memoir of Master Hubard (Philadelphia: Atkinson and Alexander Printers, 1825), https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.fl49gd;view=1up;seq=5, accessed April, 2017; Albert Ten Eyck Gardner, “Southern Monuments: Charles Carroll and William James Hubard,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, New Series, Vol. 17, No. 1 (Summer, 1958), pp. 19-23; The Johnson Collection, “Hubard, William, 1807-1862,” The Johnson Collection, http://thejohnsoncollection.org/william-hubard/, accessed December, 2013.

3. William Dunlap, History of the Rise and Progress of the Arts of Design in the United States, Vol 3 (C. E. Goodspeed Co., 1918), 257.

4. Atkinson and Alexander, 4-7.

5. Ibid.,

6. The Johnson Collection, op. cit.; Dunlap, op. cit.

7. William Gerdts, Art Across America: Two Centuries of Regional Painting, Vol. 2, The South and the Near Midwest (Cross River Press, 1990) 17-18; Estill Curtis Pennington, “Hubard, William James,” in Judith H. Bonner, Estill Curtis Pennington, eds., The New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture: Volume 21: Art and Architecture (University of North Carolina Press Books, 2013), 337-340

8. United States Customs Office, Registers of Vessels Arriving at the Port of New York from Foreign Ports, 1789-1919. National Archives and Records Administration Microfilm Publication M237, roll 38, list 332.

9. New York Historical Society, National Academy of Design Exhibition Record: 1826-1860, Vol. 1 (New York Historical Society, 1943), 241.

10. United States Census, Eighth Census of the United States. “Household of Wm. J. Hubard,” Henrico County, Virginia, August 22, 1860, National Archives and Administration (NARA) Series M653, Roll 1353, page 121, lines 5 – 8; Mrs. William B. Lightfoot, “William James Hubard,” R. Bolling Batte Papers, The Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia, biographical Card Files, Hubard, Card 65; United States Census, Eighth Census of the United States: Slave Schedules, NARA Series M653, “W. J. Hubard,” Henrico County, Virginia, August 20, 1860, page 24, lines 9-16. Other collaborations between Mann and Hubard including posing for daguerreotypes in positions described by Charles LeBrun (1619-1690) in Expressions Conference sur l’expression génerale et particulière, published posthumously in 1698.