Oil on Canvas, 30 x 25 inches

Private Collection

Louisa Watkins is the fourth post-Civil War posthumous portrait I have seen that depicts a person George Caleb Bingham may never have met or barely knew. To create the portrait, he had to rely on a photograph. The others are Sarah Ann (Sallie) Elliott (Mrs. Henry A. Neill), Julia George, and Julia’s brother, Richard Booker George. All four subjects sit facing forward, in the immovable and resolute manner that people sat before a camera in the early days of photography.

When the first one appeared, Sallie Neill, I first ruled out Bingham’s colleagues and students as the artist, and then conferred with other Bingham experts. They concurred: Bingham was the artist. I had doubts about Julia George as a Bingham until I saw her in person: she is a quintessential Bingham. The beauty the artist gave to her brought tears to my eyse.

With its widened temples, Louisa Watkins has the tell-tale “Bingham look.” Some of the Missouri Artist’s students and colleagues could mimic that “look,” which causes mis-attributions even in the present day. But, everything about Louisa Watkins from hair to lace, to fingertips speak of George Caleb Bingham. Provenance proved my theory that the Missouri Artist painted the portrait from a photograph after the sitter’s death.

Provenance

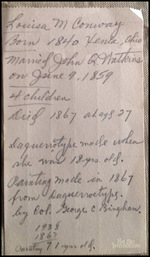

The portrait’s ownership descended through the family. According to a small document, handwritten in 1938 by a Watkins descendant, Bingham painted Louisa Watkins after her death on June 20, 1867, from a nearly ten-year-old daguerreotype.

(Conwell was actual maiden name)

Date

ca. 1867

Subject

Louisa Ann Conwell was born on August 20, 1839, in Xenia, Greene, Ohio, to Richard Conwell and his second wife, Eliza Beatty. She was the eleventh of her father’s twelve children. Her father died when she was five. As her widowed mother raised her six children and a mentally challenged step-daughter, she had the help of at least three of her older stepsons, who lived nearby with their families.((Family information derived from public records on Ancestry.com, including birth and death records, and census data on family members for the years 1840-1880.))

In the late 1850s, Louisa, along with several of her older siblings and half siblings, moved to Kansas City, Missouri. When she was 19, she met a 29-year-old businessman, John Q. Watkins. On June 9, 1859, she married him. Their first child, Judith Chevallie Watkins, was born on July 2, 1861. A year later, on June 9, 1863, Louisa gave birth to a son, John Q. Watkins, Jr.((Ibid.))

Her husband purchased Kansas City’s oldest bank in 1864. Originally founded in 1856 as Coates & Hood, with a subsidiary real estate firm, Northrup & Co., the bank was later renamed Northrup & Chick.[1] As Watkins Bank the facility moved to a new building at the corner of Main Street and 2nd Avenue.((Carrie Westlake Whitney, Kansas City. Missouri: Its History and Its People, 1808-1908, Volume 1 (Chicago: S. J. Clarke Publishing Company, 1908), 145. Later in the history, Whitney used 1865 as the date of transfer. ))

Louisa and John’s third child, Robertine Lela, was born May 10, 1865. That same year, the men of Kansas City elected John Q. Watkins to the City Council.((Early view of Main Street and 2nd with the Watkins Bank in view on the corner. Delaware Street bluff in view behind the bank, Photograph dated July 1868, Scrapbook Collection #3 – Historic Kansas City, P24, Box 1, Page 7, Number 29, Missouri Valley Special Collections, Kansas City Public Library, http://www.kchistory.org/cdm4/item_viewer.php?CISOROOT=/19th&CISOPTR=369&CISOBOX=1&REC=10, accessed November 2016.))

Louisa gave birth to their fourth child, her namesake, on May 11, 1867. The birth must not have been an easy one because a little over a month later, on June 20, 1867, Louisa died. She was 28. Her resting place is in Kansas City’s historic Union Cemetery.

After her death, Louisa’s oldest child, Judith, or Vally as she was called, 11, was sent to live in a convent school.((United States Census Bureau, Census of the United States, “Household of John Q. Watkins,” July 6, 1880; Kansas City, Jackson County, Missouri; National Archives and Records Administration Roll: 692, page 23, lines 20-21.)) Watkins’ banking partner, George Bryant, and his wife, Bettie, adopted the baby, “Lulu,” and raised the younger daughter, Lela.((Unsourced Statement in Ancestry.com, but confirmed with 1880 census, “Household of George Bryant,” Kansas City, Jackson County, Missouri, page D, lines 17-20; Watkins and Bryant partnership confirmed in Wm. Crosby and H. P. Nicholes, “Private Bankers, Missouri,” The Bankers’ Magazine, and Statistical Register, Volume 20 (Banks & Banking, 1866), 93.)) The early life of her son is not currently known, but by the age of 17, he lived with his father in rooms in or near the bank.((United States Census Bureau, Census of the United States, “Household of John Q. Watkins,” July 6, 1880; Kansas City, Jackson County, Missouri; National Archives and Records Administration Roll: 692, page 23, lines 20-21.))

John Q. Watkins never remarried. He appears to have devoted himself to business. He invested in Kansas City’s first streetcar company and in the county’s first Horse Railroad Company in 1870. By 1874 he owned a silver mill in Colorado. Eventually, he would assume the important financial role of president of the Kansas City Clearinghouse.((Whitney, op. cit., 675; Rocky Mountain News Print Company, The Colorado Directory of Mines: Containing a Description of the Mines and Mills, and the Mining and Milling Corporations of Colorado, Arranged Alphabetically by Counties, and A History of Colorado from Its Early Settlement to the Present Time (Rocky Mountain News Print Company, 1879), 193.)) Late in life, he returned to his family’s Virginia plantation. There he died in 1899 at the age of 70.((I. S. Homans, The Banker’s Almanac and Register, 1877 (Banker’s Magazine, 1877), 83.))

Conclusion

George Caleb Bingham’s good friend Johnston Lykins (1800-1876) was president of the Kansas City branch of the Mechanic’s Bank of St. Louis, Missouri. The two bankers Lykins and John Q. Watkins. Bingham may have met Louisa Watkins socially through Lykins. In May 1870, almost a year after Louisa’s death, Bingham moved into a new studio above Shannon’s Dry Goods Store at 3rd and Main in Kansas City, one block from the Watkins Bank. I suspect the artist convinced the grieving widower to allow him to paint a likeness of the woman the businessman had loved and lost. Combined with all the other evidence, the most telling feature of the Watkins portrait as a Bingham is its psychological engagement with the viewer. Bingham imbued Louisa Watkins’ after-death portrait with a gentle, almost innocent, expression, that is at the same time, enigmatic, a feat made all the more amazing since his only model was a ten-year-old daguerreotype.